Today is election day. Never in my life have I been more happy

to see an election come to an end. Instead of feeling patriotic and proud to

participate in the election of our government leaders, I cast my vote with

clenched teeth, angry and disappointed at what the process has become and

wishing that I could cast a vote of “no confidence” in the whole lot.

Reflecting on Life's moments to see what the future holds and asking "What if?"

Tuesday, November 6, 2012

Thursday, September 13, 2012

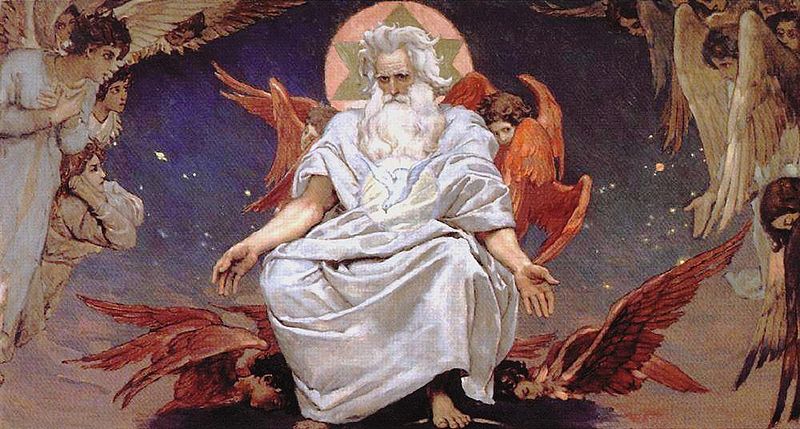

Living With a Perfect God

There seem to be many

competing images of God in the world today; a loving father, a benevolent

master, a strict tyrant, a demanding ideologue, holy perfection and many, many more. Ultimately,

our image of God is reflected in our own life. We see it in our expectations,

in the way we treat others and in the way we think about ourselves. Changing

the way we understand God can change almost everything about life.

Labels:

attitude,

creation,

disobedience,

expectations,

flaws,

garden,

God,

Jesus,

life,

Noah,

perfect,

perfection,

process,

sin

Wednesday, August 22, 2012

Fullness of Time

Some days it feels like I’m supposed to be a cheerleader at a

funeral.

Some days it feels like I am doing hospice work

with a patient who is unaware of their own impending death.

Labels:

brokenness,

change,

culture,

despair,

fullness,

grief,

hope,

lament,

new birth,

poem,

time,

waiting

Saturday, August 11, 2012

Holy Shit

At the end of July I

developed two of my previous posts on lamenting (Lament and

The

Lost Art of Lament) into a sermon. As part of the sermon I invited people

to write down their laments on a piece of paper that was photocopied to look

like a brick. The staff at church and I assembled the bricks into a “wailing

wall” that is displayed at the entrance to our worship space.

I sat down at my desk the following Tuesday and began reading

through all the laments that were emptied out onto the paper bricks in worship

on that Sunday morning. There were laments about the state of our nation and

the political process. There were laments about the civility of our society,

random violence and even specific examples taken from the news. There were

laments about the aging process, health concerns, illness, broken

relationships, and personal failures. And of course, there were laments about

the death.

When I finished reading the laments I sat quietly for a time

marveling at the resiliency of the human spirit.

Friday, July 27, 2012

The Lost Art of Lamenting

The help we need to get

through an emotionally difficult time doesn’t come from people who are not

suffering. It comes from the people who know the same kind of suffering and who

are willing to suffer with us. When we lament together as a community we admit

that we are vulnerable and, at the same time, discover that we are not alone in

our pain. That discovery often gives us the strength to work through the grief

and help others cope as well.

Labels:

alone,

community,

death,

grandparents,

grief,

grieving,

healing,

help,

lament,

Psalm 94,

rejoice,

support

Tuesday, July 24, 2012

Lament

As I return to my writing after a month-long sabbatical I am struck by the events of this summer, and especially this past weekend, that have left us shaking our heads and wondering, “Why?” From the seemingly every day tragedies reported on the news shows to the extreme cases like the shooting in Aurora, Colorado, the events surrounding the Penn State football program, and the disappearance of two young girls in a neighboring community we are faced with the various ways evil manifests itself in our life. Such a constant barrage of bad news leaves us in a precarious emotional state searching for some way to respond.

Labels:

Aurora,

cry out,

God,

grief,

healing,

health,

lament,

Penn State,

shootings,

silence,

spirituality

Thursday, June 21, 2012

A Still Small Voice

There is a voice in my

head that I believe is the voice of God. (See my previous two posts: The Voiceof God and Not My Voice.) One of the reasons I believe that it’s God’s voice

and not my own internal monologue is that I can’t control it. I can’t will it

to tell me something I want to know. I can’t even will it to speak to me at all.

Labels:

crazy,

dilemma,

Elijah,

God's voice,

listen,

listening,

monkey mind,

small,

still,

voice

Tuesday, June 19, 2012

Not My Voice

At first I was

hesitant to believe that this voice I heard in my head was the actually God

speaking to me. I’m still not one-hundred percent certain about it. At the

time, there was only one way to find out if it was or if it wasn’t God speaking

to me. So I started to listen.

Labels:

choice,

coping,

faith,

God,

institution,

life,

listening,

meditation,

peace,

prayer,

religion,

scripture,

trust,

voice

Monday, June 18, 2012

The Voice of God

Trusting God implies that we know what God wants us to do. That’s

not always so clear and it’s not hard to find different interpretations from

different people. Where is that clear voice that speaks from another realm like

it did for the people in the Bible?

Labels:

appearances,

direction,

God,

hearing,

leading,

listening,

prayer,

speaking,

trust,

trusting,

vision,

voice

Wednesday, June 13, 2012

Church Politics

Anyone who is actively

involved in a congregation quickly learns about church politics. Nobody likes

them but it seems impossible to do anything without running into them. As in

most institutions, politics in the church does more to hamper good ideas than

to help them get done.

I had been called into the senior pastor’s office to meet with

the president of the congregation.

“It appears that we didn’t follow the rules to the letter when

we called the special meeting,” the president said. “Nobody put the notice in

the local paper.”

It had been four days since the meeting and we knew that there

were people who were upset about the decision to buy a new house to serve as

the parsonage. The house was located adjacent to the church property and the

owner, a member of the congregation, was giving us an unbelievable deal. The

house was in better shape than the current parsonage and it made sense to own

the property right next to the church. The people who had been at the meeting approved

the proposal to purchase the property by a margin of 60-40.

But another member, who also had property adjacent to the

church, was upset by the decision because he had plans to offer the same kind

of deal to the church when he retired in a few years. After the meeting he went

home and combed through a copy of the church constitution and found the loophole

he was looking for. The church council had made the proposal and notified the

congregation of the meeting two weeks in advance by newsletter and in the

weekly Sunday bulletin. But nobody was aware of the by-law requiring special congregational

meeting notices to be published in the local paper. The decision made at the

meeting, therefore, was null and void and the disgruntled member was

threatening legal action if the congregation went ahead with the purchase.

While in seminary one of my professors had worked in a steel

mill as an electrician’s assistant when he was a student. He said it was

important to know how the power was designed to flow through the wires. But he

said that the electricity didn’t always flow the way it was designed to flow.

“It’s more important,” he said, “to know how the power really flows. It’s the

same in congregations.”

I am a process person. I believe that a good decision making

process helps everyone get involved and is transparent to anyone who has

questions about how a decision is made. A lot of my work as a pastor has been

to clarify and improve these processes. Nothing frustrates me as much as when a

process is agreed upon and then decisions get made outside of that process.

An elderly colleague told me early in my ministry, “A German

congregation will argue tooth and nail before a decision is made but then they

will all go along with it. A Scandinavian congregation will go along with a

proposal until a decision is made, then they will argue tooth and nail about it

in the parking lot.”

I grew up in a congregation where the former was the rule but

I’ve worked in congregations where the latter is the way business is done. It’s

a recipe for hair-pulling exasperation. I’m always embarrassed when someone

asks me who they need to talk to when they need a decision to be made. Do I

send them to the person/s that is designated by our agreed upon policies or do

I send them to the person/s who will ultimately make the decision? (These are

often different people.) Do I pretend that the process makes a difference or

should I just be honest about the way business is done?

It has been my experience in the Lutheran church that decision

making processes that are outlined in constitutions and by-laws are not

reflective of the way that decisions are really made. Talking to colleagues, I

see this to be true of most congregations not just the ones that I’ve served.

People often refer to this as “church politics” and it has the ability to suck

the life and energy out of an otherwise vibrant ministry. Unfortunately it’s

what occupies the energies of too many congregations.

In the end the congregational council had to declare the vote

at that special meeting to be invalid.

The person who owned the property withdrew the offer, not wanting to create

more contention within the congregation. The member who was upset had tipped

his hand to his intentions and basically ruined his chances of selling his

property to the church. The congregation missed an opportunity to upgrade its

property and ended up spending money to repair the existing parsonage. Nobody

came out a winner.

Tuesday, June 12, 2012

Spiritual Authority?

How do you think of your

pastor/s? Do you want them to be spiritual experts that tell you what you

should believe and how you should believe it? Or do you want them to help you

see connections between faith and life that you might be missing on your own? Do

you want someone who is an authority or someone who sometimes struggles with

faith and belief and is honest about it?

I came into ordained ministry with the idea that I would be

the spiritual authority for the people I served. I had been through four years

of post-graduate studies and had promised to uphold the theology and doctrine

of the Lutheran church. Furthermore, I found that people came to me looking for

spiritual advice and many were willing to accept what I told them as absolute

truth without another thought.

What I found out was that there are a whole bunch of people

who know a whole lot more about life and are more acquainted with the Bible

than I was. Whenever I sat down at a Bible study there was always someone who

had spent more time reading the Bible than I had. Whenever I applied lessons

from the Bible to daily life, there was someone present who had experienced more

of life’s ups and downs than I could imagine.

It was hard not to feel like an imposter. I was in my late

twenties and had just started a family and a career. How could I even begin to

talk about the relationship between faith and life? What could I tell people in

their fifties or eighties that they didn’t already know deep inside themselves?

I wondered how long would it take before people noticed that I wasn’t the

expert that they expected me to be.

This is the tension and dilemma that I live with most days. I

am trained and called to lead a community as an expert while at the same time I

am certain that I am no more an expert on the ways of faith and life than

anyone else. Yet every time someone asks, “What I am supposed to believe about ?” I’m

reminded that I am expected to be that expert.

My natural impulse in the face of this dilemma was to become

even more of a spiritual expert. I didn’t want people to think that I wasn’t

qualified to be their spiritual leader. Instead I wanted them to think that I

was able to provide something they didn’t have. I wanted them to turn to me

when they were in need of spiritual care and guidance. So in my spare time I

read more theology books and attended leadership conferences. I spoke with

certainty and confidence in my sermons and classes even though I didn’t feel

that way inside.

That I would do this based on the fear of being discovered as

a charlatan should be a clue that it is not a good impulse. Whenever I hold

myself up as an expert in faith and life I sustain the notion that a spiritual

life is a complicated endeavor filled with indecipherable theological thoughts

and language. I also give the false impression that there is one, right way to

think about God, faith and our relationship with the world. And because many

people believe that what happens to them after they die depends on making sure

they have that one, right way figured out (even though I was telling them it

does not) I was likely adding to their anxiety at some level.

When religious belief is tied to communal identity it is

important to believe the same thing as everyone else in the community. This is

the way religion has been for ages. But up to this point in history personal

identity has been tied community. Today we live in a world that is increasingly

individualistic and identity is found in things other than community. (This has

been a long and gradual change in the Western world but now accelerating and

becoming a global shift in the way we understand who we are.) Therefore what it

means to be a spiritual authority has to change as well. At best I can share

with someone what I believe to be true and perhaps help them discover what it

is that they believe. This is a very different than trying to be an expert.

These days I find myself straddling the line between being an

the expert in faith that many people expect in a pastor, and trying to be more

like a spiritual partner and guide to those who are trying to travel their own

faith journey. I find a greater sense of peace surrounding those people who

look to me as a partner and resource in their journey than in those who want me

to be an expert. Maybe that’s because of my own place of comfort or maybe they

really are more at peace. I don’t know for sure.

Friday, June 8, 2012

Soloing

Do we all crave the

attention that comes with being great at something? Does everyone have the

desire to step out on stage and solo? Or do we simply think “my way is the best

way” and long for a chance to prove it?

Having

a year as a solo pastor opened my eyes to see the way this works in my own

life. I have no doubt that I could be a senior pastor or lead my own church.

And I like to think that I would do a good job. But I can also see the ways in

which I would arrange things for my own benefit and I’m not interested in

leading a congregation just to prove that I can do it.

After serving in my first call for three years I was eligible

to receive a call to another congregation. I wasn’t in a hurry to move to a new

church but I started getting phone calls from other congregations asking if I

would be interested in interviewing to fill a vacancy. I was also recruited to

undergo an assessment to determine whether or not I would be a good candidate

to start a mission church from scratch or to lead a small congregation in a

rebuilding effort. Both of these requests required that I fill out

denominational mobility papers describing my ministry style and experience

which, in turn, brought more requests for interviews.

Many people believe that church work is like the corporate

world. They think that pastors start out as associates or at small churches and

then work their way up to a medium sized church as a solo pastor. Eventually they

move on to a larger congregation as a senior pastor. To be honest, that is the

path many pastors follow. Fortunately I enjoyed my work and my colleague and

didn’t feel compelled to move. So I did some interviews when a particular call

intrigued me but never really felt called to any of them.

It was somewhat of a surprise in my fifth year of ordained

ministry when my colleague and senior pastor called me into his office and told

me that he had accepted a call to a congregation in another state. Many people

in the parish I served assumed that I would become the senior pastor but there

were two things that stood in the way of that transition: The church governing

body prefers that this kind of “promotion” doesn’t happen and, after talking

things over with Amy, I felt that I wasn’t called to be the senior pastor of

the parish. Instead, I would serve as the only pastor while the parish looked

for a new senior pastor.

Doing the work of two pastors was difficult. That year I

presided at 14 weddings and 23 funerals instead of doing only half of those.

The parish scaled back to three worship services every weekend and they invited

pastors from nearby towns to fill in one Saturday evening service each month. I

doubled the amount of time I was in the car driving to hospitals and doing

visits since there was no one to split these duties with.

But in some ways the job was easier. The buck stopped at my

desk now. I was responsible for the day to day running of the parish and didn’t

need to consult with someone else. There was a certain amount of freedom to

shape my ministry the way I believed was right for me and for the parish. It was

also a relief from the hard work of doing joint ministry with a team of

pastors. While I was (and still am) committed to the benefits of shared

ministry it can be a frustrating and fatiguing endeavor. Having a year to be a

solo pastor while the parish searched for a new senior pastor was a great

experience.

What I discovered about the church and about myself in that

year of solo ministry is that congregations tend to be shaped by whatever

pastor or team of pastors is leading them. They tend to take on the personality

of the pastoral leadership. I also learned that this is the exact opposite of

what I believe should be the case. I believe that a congregation should define

their ministry and seek a pastor that can help them do that ministry. at one

point in the year I even mentioned this in a sermon, pointing out that it

seemed the congregation only participated in programs as long as the pastor

pushed them. But when the pastor left there didn’t seem to be any interest in

continuing the program. Someone actually told me, “It’s nice to see someone

finally figure it out.”

In the years since this discovery I have become more convinced

that congregations relinquish this responsibility to their pastors who

willingly accept it as their own. Congregations are thus shaped in the image of

their pastor. Sometimes this is referred to as the pastor’s “vision” for the

congregation. But no matter how well intentioned a pastor is, it’s difficult

not to structure things in such a way as to ensure that the power to shape a

community is retained in the office of the pastor. Pastors working together

with congregations in a healthy, mutual ministry is not as common as those in

the church would like to think.

Labels:

call,

community,

congregation,

gifts,

image,

interim,

ministry,

pastor,

self,

shaping,

sharing,

Solo

Thursday, June 7, 2012

Learning to Preach

We all try to fall into

a groove where life becomes more manageable and we can be comfortable. But then

something happens to move us out of that comfort zone and we have the opportunity

to learn and grow. When that happens we are faced with a choice: Do I return to

the old way as soon as possible or do I take a risk and open myself to a new

way of being in the world?

At the three-point parish where I started ordained ministry,

the senior pastor and I presided at four worship services every week. One of us

would lead worship at the two churches in town on Sunday morning. The other

would be at the Saturday evening worship in town and then drive to the country

church on Sunday morning. We would do

this for a month and then trade. This rotation meant that I had to write and

deliver a sermon every week. Most associate pastors don’t get to preach that often

or even close to it. Since I enjoy preaching it was a great opportunity to do

something I felt I was good at. The frequency also helped me get better.

Coming out of seminary I worked hard to craft each sermon,

carefully choosing phrases and editing my words until they were just right (or

until I ran out of time and couldn’t work on them anymore). Having put all that

time into them I would print them out on the dot-matrix printer connected to my

computer, double spacing them so that I could easily read from my manuscript as

I stood in the pulpit. I would rehearse by reading through a sermon two or three

times before worship, making sure I was able to look up from my text and make

eye contact with the congregation. This, I was told in preaching class, made it

more personal for the people in the pews. At the end of the first service I

would greet the worshipers at the back of the church, pack my bible, sermon,

and whatever else I needed into my briefcase and take it all with me to the

next service.

If I was in town for the month the drive was just six blocks

to the next church. If I was going to preach at the country church it was a

beautiful, winding drive through the hills, valleys and farmland of western Wisconsin

that took between 15 and 20 minutes. It was, of course, one of the days when I

was at the country church that I arrived for worship and discovered that I had

left my sermon manuscript sitting in the pulpit after the Saturday evening

worship.

I dug through my briefcase one more time hoping that it would

miraculously appear. Looking at the clock I did the math with the sickening

realization that I didn’t have time to run back into town and retrieve my

sermon. It occurred to me that I could send someone from the congregation into

town but there was no guarantee that they would be back when it was time for

the sermon. I either had to explain to the congregation what had happened and

tell them there would be no sermon that day, or I would have to preach from

memory. I chose to risk the embarrassment of preaching from memory, possibly forgetting

part of the sermon over the embarrassment of admitting that I was unprepared.

When it was time for the sermon, instead of stepping up into

the pulpit, I descended to the floor in front of the congregation. In that old,

country church the pulpit was a raised platform that jutted out from the front

wall above the congregation. Whenever I stood in the pulpit my feet were at eye

level with the worshipers sitting in the pews. The architectural design was meant

to be impressive and authoritative. Stepping down to be at the level of those

in worship had a very different feel; definitely more casual but more intimate

too. Instead of being someone who stood over them I was standing among them. I

realized the symbolism and significance of that gesture immediately.

As I preached that day without manuscript or notes I

discovered a sense of freedom. I had been using my manuscript as a crutch. I

knew what I was preaching but was too worried about the exact way in which I

said things. I knew the points I wanted to make and the illustrations that I

had chosen to make those points. I had been telling stories by memory for years

and a sermon is simply a story of how we understand something written in the Bible.

By stepping away from the manuscript I sounded more like myself. Preaching

became a personal thing, a way of sharing what I understood about the text,

faith and life.

The encouragement I received after the service caught me off

guard. The sermon I preached was not as concise as my regular sermons with a

manuscript, but it seemed to have struck a chord with those in worship that day.

Sheepishly, I admitted the real reason behind the change in preaching style

while in my mind I committed myself to making the change a permanent one.

Noted media professor Marshall McLuhan said that “the medium

is the message.” Preaching a sermon from the heart, without notes, sends a

message to the listener beyond the meaning of the words. For me it meant more

work rehearsing what I wanted to say. It also brought a change to the way I

prepared sermons. I no longer spend time fretting over exact wording in front

of a computer screen. Instead, I spend time listening to the words that come

out of my mouth, wondering how I would hear it if I were sitting in the

congregation.

Had I never left that manuscript in town I might never have

discovered the style of preaching that works so well for me. In the years since

then I have continued to experiment with that style, searching for my voice in

a world that is ever changing.

Tuesday, June 5, 2012

Speaking for Others

A colleague once pointed

out to me that pastors speak to the congregation as the voice of God in sermons

and we speak to God as the voice of the congregation in liturgy and prayers. I

still fight within myself to do these things with any sense of honesty and

integrity.

“Pastor, would you mind giving the blessing?”

“Pastor, could you open our meeting with a prayer?”

“Pastor, when you go to the hospital can you stop and have a

prayer with ?”

At first it feels like an honor. People turn to me for

something they want and it feels good to be of service. I am valued and looked

up to. People wait for me to say something to God, to ask for something from

God and I like it. It’s what people expect a pastor to do. It’s what I’ve been

trained to do. And it doesn’t seem to be that hard. At first.

There are Psalms and prayers written in the little books that

pastors keep in their pockets. There are prayers for blessing a house, for

losing a job, for relocating, for people who are sick, people who are dying,

people who are getting married or divorced or having a child or just about

anything else a person can experience in this life. All I have to do is find

the right page and insert the person’s name in the blank as I read it.

But sometimes this doesn’t work. These specifically generic

prayers don’t quite speak to the exact issues at hand so I begin to develop my

own prayers. I learn to ad-lib. Good sounding petitions get repeated and before

long I have a list full of phrases that can be mixed and matched to sound like

fresh prayers straight from the heart. This, by and large, seems to work. It

might not be completely genuine but it becomes my “style” of praying.

I begin to wonder though, “Why am I the only one who prays out

loud in a group setting?” I’m aware that my prayers reveal one perspective; my

own. Where is the voice of elderly wisdom? Who is giving voice to the feminine viewpoint?

How can I speak the grief of someone who’s child or spouse has died when I’ve

never experienced that? I can ask God to be with and bless these people but how

can I ever truly be their voice?

It seems right to let others pray too. But when I ask for a

volunteer to pray on behalf of a group that is gathered, there is a moment

where it feels like I’ve requested a volunteer for a suicide mission. The

problem with public prayer is that it is extremely self-revealing. When we pray

out loud other people get a glimpse into our soul, into our most personal and

private beliefs. When we pray in front of others we risk exposing our deepest

doubts, fears, longings and joys. And the truth is, we don’t like being exposed

like that in public.

I realize that as a pastor I’ve learned how to hide behind the

prayers I say in front of other people. I’ve learned how to construct prayers

that are theologically correct but not true expressions of my own feelings. I’ve

learned how to create formulaic prayers that sound good to the ear but never

speak to the heart. I’ve learned how to pray with bold confidence but have

never been willing to pray with the uncertainty that lurks below the surface.

What would that be like?

Labels:

correctness,

disappointment,

groups,

honesty,

hope,

integrity,

pastor,

personal,

prayer,

priest,

private,

public,

speaking,

uncertainty

Monday, June 4, 2012

Thin Places

There are places and

times when we feel a deeper connection to all of life; past, present and

future. I was once told that the Irish call them “thin places.” Births, deaths

and ritualized transitions like weddings and baptisms often bring us to those

thin places where we experience pain, wonder, hope and joy all at the same

time. As a pastor I have had the privilege to be present when families invite

me to be with them in these sacred moments.

The first memorial service I ever did for someone was at the

request of the deceased’s girlfriend. When I sat down with her to talk about

the service I learned that her boyfriend died in a car accident while running

from the police because he was on parole and there were drugs in the car. He

was on parole after serving time for setting a local church on fire to hide a

robbery. When I finished the service I thought that was the strangest funeral I

could ever imagine.

Not even close.

The next one was for an elderly man whose grown daughter had

Down’s Syndrome. Her brother had wrapped their dad’s ashes in a gift box so as

not to upset his sister. Instead, she thought the present was for her birthday

and she spent most of the service begging to open it and throwing a fit when

her brother wouldn’t let her.

Another time I was asked by one of three sons to preside at

his dad’s funeral. About half-way through the service, at the conclusion of the

sermon, the eldest brother stood up and said, “Dad didn’t believe in this

bullshit but he loved his beer. We’re takin’ this celebration down to the bar.”

And they did.

At another funeral the cement vault wouldn’t go all the way

into the grave. The funeral directors and I spent 15 minutes jumping up and

down on the vault to get it to settle below the surface after the family had

gone back to the church for lunch.

And it would have been nice if someone had told me that when a

person dies it doesn’t always happen like it does on TV and in the movies.

Involuntary muscle contractions sometimes cause the lungs to gasp for air for

up to two minutes after death. Nobody wants to hear the grown man in the

clerical collar scream like a little girl in the peaceful and solemn moments

after grandma passes away.

I’ve presided at weddings where the rings were left in another

room and more at more than one where the Unity Candle wouldn’t light or ring

bearers and flower girls refused to walk into the church. At one wedding, the

bride looked at me during the vows and I thought she was going to run. At an outdoor

ceremony the Unity Sand was missing so the bride’s aunt walked to the parking

lot to retrieve it and then tried to sneak it into place behind me during the

service while everyone watched what she was doing instead of paying attention

to the couple as they said their vows.

I have seen grandparents act like paparazzi, standing in front

of the congregation with cameras flashing to capture the exact moment when a

grandchild is baptized. I’ve seen parents of baptized infants stand like stone

statues while an older child distracts everyone, exploring the front of the

church.

You might think that these are not sacred thin places but they

are. We long for moments when we experience the eternal. But even when things

go exactly as planned we still bring our humanity with us into those moments.

Sometimes our fear and insecurity cause us to balk in the presence of the

eternal. Sometimes our excitement and joy can’t be contained. But most of the

time it’s simply because we are human and we have no choice but to bring our humanity

into these thin places.

The fact that our human foibles can’t ruin these thin places

makes me think that perhaps there are way more of them than we realize. Maybe

we encounter thin places every day and we just miss them because we are too

caught up in the drama of the world around us.

What thin places have you experienced? Will you run into one today?

Labels:

birth,

death,

foibles,

funerals,

holy,

humanity,

humbleness,

life,

sacred,

Thin places,

weddings

Thursday, May 31, 2012

A World of Expectations

We are born into a world

of expectations. People expect us to think and behave certain ways because of

who they think we are. There are expectations based on our culture, our gender,

our social status, financial status, educational level, age, occupation and

religion. When we try to break out of these expectations and discover who we

really are we can cause great distress for others.

Recently, in front of a large group I was asked what I

disliked the most about being a pastor. My response? That I’m always a pastor

wherever I go. People treat me differently because I am a pastor. Some treat me

with more respect than they show other people and some treat me with less.

Usually the only time people treat me like a regular person is when they don’t

know I’m a pastor.

When I first started my life as an ordained pastor I tried to

live up to all of the expectations. I dressed like a pastor, wearing shirts

with clerical collars on Sundays and other official occasions like weddings and

funerals or when I would visit homebound members. I was careful to not have a

beer in public or to swear when something went terribly wrong. I worked hard to

keep my emotions in check and appear to be in control at all times. As a brand

new pastor I also made every effort to convince people that I knew everything

there was to know about faith and theology.

It wasn’t long before I realized that I didn’t want to live

like this, nor could I. People where getting to know Pastor Kevin but not me.

Then one day I realized that God didn’t call Pastor Kevin to ministry but that

God wanted Kevin. If God was okay with who I was and called me to ministry then

it would be okay to be me and in ministry.

That’s when things started getting a lot harder.

It turns out that people don’t want their pastors to be

ordinary people. They want their pastors to be shining examples of virtuous

living and paragons of faith. And furthermore, they will go to great lengths to

make sure you live up to those unrealistic expectations or they will make your

life miserable.

One Sunday morning I was preaching a sermon about spiritual

gifts teaching about the gift of Mercy. A person with the gift of Mercy has the

ability to recognize when someone is hurting and is able to empathize with the

hurting person and find ways to comfort them. Many people have this ability,

including people who aren’t religious. As an example I told a story about

another pastor I knew who was able to look out over her congregation during

worship and identify those who were suffering. She would then quietly say

something to them after the service or would be sure to call them the following

week. I, on the other hand, do not have the gift of mercy. I tend to be

oblivious to the signs and the depth of people’s pain. I shared that I was a

envious of this other pastor’s ability but I believed that there were people in

our own congregation who had that gift and God was calling them to use their

gifts.

The following week I met an elderly woman who had been caring

for her disabled husband for years as he continued to decline. By and large she

seemed to be a rather timid person but on this particular day she attacked me

with the tenacity of a mother tiger protecting her cubs.

“Don’t you ever say that you don’t have the gift of mercy,” she

said, wagging her finger at me. “Pastors

are caregivers and if they aren’t then who can be? I don’t want to hear you

talk like that ever again.”

At first I thought that she was afraid that I was being too

hard on myself. As I tried to assure her that it was okay and that I had been

given other spiritual gifts she interrupted.

“No! Don’t say that,” she pleaded. “You are a wonderful

caregiver and have been great to my husband and me.”

That’s when I started to realize that she had to believe something

that was not true about me in order to allow me to serve her. She couldn’t bear

to think that she was getting less than the best care in the world. It was the wrong time to correct her false

image of me. But playing along meant that I wasn’t free to be the flawed person

I am. It meant I couldn’t live in the truth of who I was.

Unfortunately, this wasn’t an isolated incident. I, and other

pastors I know, are constantly bombarded with expectations to be someone or

something we are not. Fighting those expectations takes energy that we would

rather put into helping people. So too often, we take the path of least

resistance and put up a façade and play along with the expectations until we

either begin to believe them ourselves or until we are burned out. Either way

it leads to a bad end.

Pastors aren’t the only ones caught up in a world of

expectations. The only way out is to be honest with ourselves and live with

integrity and openness until those who try to make us into something we are not

face the issues within themselves that cause them to mold us in their image.

Wednesday, May 30, 2012

Two Themes

When we find ourselves

struggling with something in life it’s both amazing and a little depressing to

realize just how long we have been dealing with that issue. Two themes that I

thought were recent developments in my ministry turned out to be present even before

I was ordained.

As

I continue retracing my journey into ordained ministry these themes will loom

ever larger in my thoughts to the point where they are of great concern to me

today. Hopefully this task will take me closer to some kind of resolution or at

least give me some insight about where to go next.

My first call as an ordained pastor was to a parish of 800

members that was made up of three individual congregations that worked

together. Two pastors served the congregations. (The Senior Pastor had been

called to the parish just a month before I was interviewed. I was to be the

Associate Pastor.) There were two churches in town, just six blocks apart from

each other. The third congregation was located about seven miles from town and was surrounded by dairy farms. Each

congregation had their own budget and leadership councils. There was also a

parish budget that each congregation contributed towards based on their

membership as well as a parish council that had representatives from each

church.

In the Lutheran church each congregation issues a call to a

qualified pastor. This is done after a series of interviews. During the on-site

interview I was given a tour of the town, was walked through the parsonage

(church owned house) that would be our home, and was shown each of the three

church buildings. The first church was the largest of the three and hosted the

parish offices for the two pastors and the part-time secretaries. The second

church I visited was the country congregation and the third that we visited was

the church that owned the parsonage in which we would live.

At the country church I noticed a large portrait of a man and

a woman in the fellowship hall. By their attire the portrait looked to be about

twenty years old and I assumed that it was someone who had donated something

significant to the congregation. At the third church we visited I noticed the

same portrait hanging in an overflow area where it could be seen by all those

who were in worship. But this time I wasn’t left to guess who it might be.

The 72 year-old man who was showing us around walked me right

over to the portrait and said, “This is Pastor Urberg and his wife. He and his

father served as pastors to this church and several others for 80 years. The

parsonage was built the year he was born and he lived in it all his life except

when he went to college and seminary. He was the mayor in town and the street

outside is named after him. He died while still serving as pastor, just like

his father, and his widow still attends church here. The last pastor we had

didn’t think this picture should be hanging here. What do you think?”

At the time I knew that I was being tested. It was obvious.

And I was aware that the test wasn’t about the former pastor or their loyalty

to him. It was about whether I would accept them the way they were or if I

would force them to become something else. I don’t recall my exact words but in

my answer I tried to honor the tradition and the path that particular

congregation had travelled.

What I didn’t realize then was that this episode would introduce

two themes that I have struggled with throughout my ordained ministry. First is

the theme of tradition and legacy. As a pastor, I stand on the foundation of

more than 4000 years of recorded thought, debate and reflection on the meaning and

purpose of life. This accumulation has been passed on to me through ritualized

tradition and theological education. The problem is that the rituals and the

way of thinking about the essential Truth that is contained in the tradition are

not as timeless as the Truth itself. New rituals and new ways of thinking about

and expressing the Truth are needed in order for what is True to be passed on.

The second theme highlighted by this episode is my struggle with

what it means to be a pastor. Pastors are servant leaders, which means a

congregation has to take ownership for its own ministry. The congregation has

to determine what its purpose is and how it will function in the wider world.

Unfortunately, most congregations are willing to let the pastor decide.

Charismatic personalities can grow large churches because they are able to

convince people to follow their “vision.” But there is danger in letting one

person, no matter how well-intentioned they are, define the identity and purpose

of a whole community.

Labels:

call,

community,

congregation,

legacy,

ministry,

ordained,

pastoral,

ritual,

role,

tradition,

Urberg,

veneration,

vision

Friday, May 25, 2012

Approval

Is there anything harder

in life than realizing your fate is in the hands of someone else? Whether it is

an illness that can only be treated by skilled physicians or a jury that can

vote you up or down, we all face times when we have done all that we can and

then have to trust that someone else will do the right thing.

Every candidate for ordained ministry in my denomination has

to be sponsored by one of the local synods of the church. (Synods are

geographical groupings of churches in which a Bishop is given oversight to help

them work together.) During my four years of seminary I met annually with two

members of my Candidacy Committee. The meetings are meant to be encouraging and

supportive, and they are in many respects, but it was also stressful. Knowing

students who had been denied approval for ordination after four years of

seminary and all the other requirements made the process that much more nerve-wracking.

Additionally, two members of the faculty would be brought in

to meet with the student and the candidacy committee. Their job was to vouch

for the academic success of the student. They asked probing theological

questions about the connection between what we were learning in class and how

we would apply that in ministry. In my case, the faculty members liked to play

good cop, bad cop. One would ask convoluted questions about ministry that I

could barely understand and the other (my academic advisor) would rephrase my

convoluted answers so I actually sounded pretty good. I don’t know if this was

everyone’s experience or if I simply had one good member of the faculty and one

bad.

At the end of my time at the seminary I was faced with one

last hurdle. I had to appear before the entire candidacy committee and the Bishop.

The meeting took place at the Synod office and I was one of about four or five

candidates that were being interviewed that day. Because it was a two hour

drive to get there, I had arrived at the Synod office early. As I sat in the reception

area and waited I thought about the way my entire future and everything I had

worked for the past four years was in the hands of a roomful of people who

barely knew me.

Forty minutes after she was scheduled to begin her interview,

one of my fellow candidates came out of the conference room pale and sweating.

She sat down and slumped with exhaustion. When I politely asked how it went she

replied, “That’s the most horrible thing I’ve ever been through. Good luck!”

Yikes! That was not what I needed to hear. But it felt like I

would be prying if I asked her anything else. So I nervously sat with her as

the committee discussed her approval among themselves. In a few minutes she was

invited back into the room to hear the verdict. All I could do was wait for my

turn.

When the door to the conference room opened the Bishop quietly

escorted her to the front doors of the office and spoke quietly to her. She

nodded, turned and left the building. The Bishop then faced me and said, “Are

you ready Kevin?” and bounded across the

room with his hand extended to welcome me.

Inside the conference room I was shown to a seat directly

across from the Bishop on the long side of the table. The rest of the committee

members were getting to their seats after bathroom breaks and coffee refills.

The Bishop introduced everyone at the table and briefly outlined the procedure.

The first question came from the seminary faculty member on

the committee. I kept my answer brief. If he wanted more he could ask a

follow-up question but I wasn’t going to hang myself by talking at length. The

second question came from a committee member I had never met. Something in my

answer prompted the seminary professor to ask for clarification. As I felt

myself beginning to sink under the waves of judgment, and before I could

respond, the Bishop interrupted.

“Let’s cut to the chase. Kevin, we know we’re going to approve

you for ordination. What we want to know is if you can serve in the same synod

as your dad. I’d like to have you be a pastor here in this synod.”

“My dad and I get along well,” I said. “I think it would be

best if I wasn’t in a neighboring town so I can develop my own style of

ministry. But I know I would enjoy seeing him at synod assemblies and

conferences.”

“Well then,” the Bishop continued, “I don’t see why we need to

take up any more time with this. Why don’t you have a seat in the reception

area while we make this official and we’ll call you back in here in a few

minutes.”

And with that, I was approved for ordained ministry. I can’t

describe the relief and elation that I felt. It had been a long journey from

the first day I sensed the call. And it would be several more months before I

would actually be ordained. There were a few hoops left to jump through but

they were minor.

Thursday, May 24, 2012

Something Completely Different

Some of the hardest

things in life to see are the incongruities that we have been taught to

overlook. Life is filled with actions, symbols and meanings that contradict the

things we claim to believe. Becoming aware of these contradictions and

resolving them can be both heart breaking and liberating.

I

am frustrated by the incongruities and the lack of clear vision within

religious systems. And yet such uncertainty seems to hint at much greater

liberty for individuals and communities than most of us expect. Opening our

eyes to the contradictions between our personal (and corporate) actions and beliefs,

being able to laugh about them in a forgiving way, and making adjustments to

resolve them is the way towards peace.

The seminary is an accredited institution of higher learning.

Pastors graduate with a Masters of Divinity degree but the seminary can also

grant other Masters degrees as well as Doctorates. So in the spring of every

year, those who have fulfilled all the necessary requirements get to

participate in commencement exercises.

My graduation from

seminary took place at Central Lutheran Church in downtown Minneapolis. Central

is a huge, cathedral-like building with gothic architecture, ornate wooden

carvings and magnificent acoustics. It’s a church building that was meant to

inspire the worshiper and magnify the wonder of God. The seminary used the

church for graduation ceremonies because it was one of the few churches in the

area that could hold all the graduates, faculty and guests.

Because I played tuba in a brass ensemble that performed at

graduation, I had been to the commencement ceremonies in the past. One of the

traditions of the ensemble was to let the graduating seniors choose a song from

the group’s repertoire that would be played as part of the prelude. As a tuba

player I love John Philips Sousa marches and, since there were a couple in the

collection of songs that we played, I requested “Liberty Bell March.”

When we got together to rehearse for graduation I was not

surprised to be informed that my request had been turned down. I was, however,

annoyed by the short, but stern rebuke from the campus pastor who sat next to

me in the group and played baritone.

You see, Liberty Bell March is the theme song from Monty

Python’s Flying Circus. Most people don’t know it by name but when you hear it

you immediately think of the irreverent comedy show. Someone on the worship

planning team caught it and didn’t see the humor. Not only did my request get

rejected but as a punishment I wasn’t allowed to make another request. I

remember something being said about the seriousness of the occasion, apparent disrespect

to my classmates and the whole seminary community, and disappointment that I

would try such a prank.

I thought about playing dumb at that point but I didn’t really

care. It would have been so amazing and

more than fitting, in my mind, to hear the strains of the Liberty Bell March

echo through that august sanctuary right before my graduating class processed

in. The only thing that would have made it even remotely better would have been

to shout “And now for something completely different” immediately before we

launched into the song.

To me this was more than a prank. It was a statement about

everything I had been through in seminary. It was about the hoops and hurdles.

It was about the seriousness with which the church and its leaders tend take

themselves. It was a statement about the silliness of the whole commencement

exercise compared to what we were being asked to do as pastors. It was about

the incongruity of graduating in a building that was the showpiece of 19th

century, urban church architecture and the reality of being sent to serve in

rural churches with cracked walls, crumbling foundations and mildew issues. It

was about the sheer audacity to put on this show of pomp and circumstance highlighting

our mastery of a theological education without the slightest hint of irony in

claiming that we were going out to be servants.

There are other places where the symbols of master and servant

clash in the church . The stoles that pastors wear over their robes represent

the yoke of Christ and are a symbol of a servant. Clerical collars that peek

out from under the same robes are modernized versions of the collars professors

wore in centuries past to symbolize their authority and learning. We are taught that these are symbols of the

“office” of ministry so we overlook the way they contradict each other. But you

can’t be both master and servant at the same time.

Wednesday, May 23, 2012

A Prophetic Voice pt. 1

There are times when we think

we are joking around but in reality we get glimpses of deeper truths. Perhaps this is just a way for us to become

aware of ideas that are too much for us handle at the time. Returning to that deeper truth later can be

less daunting because of the non-threatening way in which we were introduced to

it.

My third year of seminary education was a year-long internship

at a congregation in Marin County, California. Working full time in parish

ministry I hit my stride and knew that all the hoops and hurdles of seminary

that I had to go through were going to be worth it.

It was the winter of that internship year that I received a

phone call from a young woman representing the Alumni Relations department at

my college alma mater. They were putting together an Alumni Directory that

would, they claimed, help graduates of the university to stay connected. It

was, of course, a thinly disguised effort to collect information that the

university could use for promotional and fund-raising purposes.

Four months earlier I had filled out a questionnaire for the

directory and this was a follow-up call to make sure they had all the right

information. She verified my address, the year I graduated, and my major. But

when it came to my occupation, instead of telling me what I had written on the

form she simply asked, “And what is your occupation?”

I smiled, remembering what I written on the card. I didn’t

want to say that I was a student. I wasn’t a pastor yet either. I was serving

as a pastor but I wouldn’t be ordained for another year-and-a-half. So on the

blank line behind the word Occupation: I had written, “Prophet.”

It was a smart-alecky answer that I knew wouldn’t fit into any

of the categories the university would publish publicly. There were no pictures

of prophets in the catalogs or brochures the university sent to prospective

students. When people think of prophets they conjure up images of street corner

nut-jobs dressed in dirty clothes, pointing fingers, waving a Bible and making

dire predictions about end-times through a megaphone. I had also hoped that

this would lead someone in the alumni relations department to put me on a list

of people who were unlikely to be a source of charitable revenue.

The young woman hesitantly asked me to spell it, as if she

wasn’t sure she heard right. More likely she was concerned that she was on the

line with one of those nut-job, college campus doomsayers who somehow managed

to squeak out a degree between his lunatic rants in front of the library.

“P-R-O-P-H-E-T,” I obligingly spelled out for her and then listened to

concerned silence from her end of the line a thousand miles away.

Have you ever said something in a completely innocent way,

goofing around actually, and when you hear it spoken out loud you become aware

of the truth buried in the words? That moment on the phone felt like one of those transparent moments in a Stephen King novel

or an episode of the Twilight Zone when the main character makes a remark that

will be taken to drastic extremes sometime in the near future with chilling

effect. I remember having this vague thought that I was playing with fire.

Writing “Prophet” on the card that I had sent in didn’t seem

like such a big deal. Saying out loud and it over the phone to someone made it

more real. It took on a certain weight and seemed to actually materialize there

in the world. A little voice inside my head asked, “What if it’s true?” I

stopped pacing through the kitchen and realized that it might be true and not true

at the same time. The seed of truth was there but it was not yet fully grown.

Today I am wondering if it’s time to revisit that premonition.

What would it look like to be a prophet

in this day and age? What message would such a prophet bring? Is it possible to

be a pastor and a prophet at the same

time? Twenty years ago I wasn’t ready to wrestle with these questions. But the

idea has been germinating for a while now and it doesn’t seem as far-fetched as

it once did.

Labels:

alumni,

college,

future,

internship,

joking,

prophet,

realization,

seed,

smart ass,

speaking,

truth

Tuesday, May 22, 2012

A No Win Situation

Sometimes we find ourselves in a situation in

which there is no possible way to succeed. What

are we supposed to learn from those experiences?

To avoid them? To endure them? To make the best

of them? Or is there another lesson lurking in the

failure?

One of the hoops that I was required to jump through in

seminary was a 10 week stint as a chaplain intern at a hospital. Clinical

Pastoral Experience (CPE) was designed to introduce us to working with people

who were sick and/or dying. But CPE was also used as a means to expose each intern

to the personal issues within us as we ministered to people. In addition to

meeting patients and serving their spiritual needs, six of us would meet with a

full-time Chaplain to review our work. The goal, it seemed to me, was to have

each intern break down and sob in front of the group so they could be lifted up

and supported. Definitely not my learning style.

I didn’t like being a

chaplain. I didn’t like going into a room and asking if someone needed some

kind of spiritual tending. I am extremely thankful for the men and women who do

this kind of ministry every day in the military, at hospitals and at care

centers. But for me it seems too impersonal. It’s spiritual care based on the

model of medical care in our culture. Each component of a patient’s health

(mental, physical and emotional/spiritual) is handled by different teams of

experts that are each trying to fix

what’s wrong with the patient. Maybe I didn’t understand what was really

expected of me but it seemed like I was being asked to join in a team effort to

treat what was wrong with each patient.

Feeling ill-equipped for this role I spent my days doing the bare minimum to pass my CPE course.

I would see the people who requested visits and chart anything I thought was significant

to help the doctors. I would meet the new patients on my assigned floors. Then

I would hide out in the medical library or a visitor’s lounge and write

verbatims (word for word transcriptions of visits I did with patients) for my

group of peers to pore over and critique.

I feel bad about hiding

when so many people needed help but I was certain that a 10 minute chat with a

seminary student wasn’t going to do much more than calm them down for the rest

of the afternoon. Maybe that was enough for that moment but I could see they

needed more. Most patients on my floors were dealing with life-threatening

ailments like cancer, brain tumors, diabetes or emphysema. Whenever I entered a

room I frequently sensed two competing expectations: One was the expectation

that I was there to heal them. The second was that I would do it as quickly and

efficiently as possible. What they wanted was a

quick fix. What they needed was a healing presence that lasted more than

10 minutes. Very often, what they needed was for someone to walk with them

slowly through their suffering.

The trouble was that I wasn’t able to do either of these

things.

I have seen the power of grace at work to calm and relieve an

anxious heart instantly so I know that spiritual healing can come quickly. But

all too often a carefully chosen quotation from the Bible can come across as

trite and meaningless, especially to someone struggling with their faith. We tend

to use Bible verses and theology like spiritual Band-Aids when the patient is

hemorrhaging. We want them to work like

magic because we are just as uncomfortable in the presence of suffering as the

person to whom we seek to give aid. While I was comfortable reading scripture

to those who requested it, I didn’t have a go-to verse that miraculously set

everything right.

Neither did I have the time to sit and chat about seemingly

trivial matters and let the bonds of companionship grow. I know I can’t be all

things to all people. But I met a lot of people who had no one in their lives

who truly knew them. Sometimes it was because the person who did know them

passed away. Sometimes it was because they were guarded and didn’t ever let

anyone get to know them. Sometimes it was because they had been abandoned by

family and friends for various reasons. All

I know is that I couldn’t give them the time and attention they needed to feel

loved.

In CPE I was put in a situation where I was set up to fail. It

was not possible for me to give people what they wanted the most and what, at some level, they needed the

most.

I thought that parish ministry was the answer to that dilemma.

In parish ministry I would be able to take the time to get to know people. But

I am finding that the conditions that existed in CPE now exist in the

congregation. The demands of my job restrict the time to truly connect with the

1300 people in my congregation or even a significant fraction of them. And

while applying scriptural Band-Aids is all that many people seem to want;

something to patch up their spiritual dis-ease, I don’t feel comfortable

leaving it at that. I don’t believe faith is meant to work like that.

So is there some lesson that I’m missing in all of this?

Labels:

band-aids,

CPE,

expectations,

faith,

hospital,

lessons,

love,

no win,

question,

quick fixes,

seminary,

suffering

Tuesday, May 15, 2012

Hoops & Hurdles

One of the frustrating things on the road to achieving our

goals is that there always seems to be some sort of requirement that needs to be fulfilled to

satisfy someone else. While these requirements are often put in place with the

best of intentions they can easily become bureaucratic hoops that take more

time and energy to jump through than they are worth.

The report from the chair of the Evangelism Committee took

less than a minute of the council’s time. “Most of the people in the

neighborhood are either black or Indian, and they have their own churches they

like to go to, so there isn’t much for the Evangelism Committee to do.”

I sat up in my seat, ready to take the chair of the Evangelism

Committee to task for missing the whole point of evangelism. Besides, there was a less-than-subtle

hint of racism buried in his observations. The pastor of the congregation, who

was sitting next to me at the table, pressed his hand against my leg to get my

attention. He silently mouthed the words, “Not now,” and shook his head ever so

slightly. Reluctantly, I held my tongue.

For my Contextual Education class I had been assigned to an

urban church on the north side of Minneapolis. It had thrived in the city

expansion of the post-war 1950’s. But in the 1960’s and 70’s an exodus of

people to the suburbs started a steady congregational decline. The people who

moved into the neighborhood didn’t look or live like the affluent suburbanites

that returned to their home church every Sunday morning. By the time I was

assigned to the church in 1989, the beautiful sanctuary that was capable of

seating over 400 people, regularly hosted about 60 every week. Most of the

Sunday school rooms had been repurposed for special groups since only four of

them were used for their intended purpose. The gymnasium echoed with emptiness

every time I passed by in the hallway.

The point of contextual education is similar to teaching

practicums for people who are studying to become teachers. Even though everyone

has been in a classroom as a student, being the teacher is quite a different

experience. Sitting in a pew every week and teaching a Sunday school class is

different than being a pastor. Since the seminary is responsible for training

qualified pastors, making sure that people know exactly what they are getting

into is important. Contextual Education is the way to do that.

But Contextual Ed assumes that a person has never been on the

business side of the church. For many people this is true. But some people came

to seminary with years of experience in congregations. They were aware of the behind-the-scenes

squabbles, the infighting and the politics of local congregations. They had

years of teaching and leading experience. Yet they too were required to work

with a church.

I was probably somewhere in between. I had experience with the

inner workings of a congregations having spent so much time in churches. What I

needed was experience leading the leaders. Leaving someone unchallenged when

they were so clearly in the wrong about the church and about the people who

lived in the neighborhood was not the kind of training I needed. This was a

teaching moment for everyone at the table. It demonstrated the kind of thinking

to which so many churches adhere. Unfortunately, the chance to inspect the

speck in our own eye, so to speak, silently slipped by.

With any experience in life there is an opportunity to learn.

I met some wonderful people in that congregation who were genuinely loving and

worked in unofficial ways to reach out to the surrounding community.

But there were some in my class who didn’t need Contextual Ed experience

because they had it before they came to the seminary.

I will admit that some requirements for certification or

graduation that felt like hoops at the time ended up being valuable learning

experiences. I don’t always know what’s best for me at the time. But creating

one-size-fits-all models of education can waste a lot of valuable time

and energy as people find themselves jumping through hoops and fulfilling

requirements that don’t teach what they are meant to teach. It’s simply a way

of making it fair to everyone. Creating individual learning programs for

students is more work for the educators but it is not impossible.

Monday, May 14, 2012

The Harrisville Incident

It was one of those mornings. We had moved to St. Paul,

Minnesota so that I could begin my seminary studies. The first course was a

summer-long class to learn ancient Greek. I had made it through two-thirds of

the course but was struggling with this last part. On this particular day I overslept

and awoke with just enough time to throw on some sweats and a baseball cap and

hurriedly walk to campus to get to class on time.

When I got to class the professor returned the quizzes we had

taken the previous day. I looked at my score and thought to myself, “This is

why I took the class pass/fail.” I had no trouble learning vocabulary but the

syntax and grammar of the language stymied me. I was frustrated at my inability

to do better no matter how hard I studied.

At the conclusion of class I debated over whether I should go

home or attend the daily chapel service. I could return to my apartment,

shower, dress and be back in time for my next class (a second helping of Greek)

but the idea of going to chapel appealed to me too. Maybe I would find some

peace there. Maybe God would speak to me through the music or the sermon so I

wouldn’t feel like I was messing up my chance to be a pastor. The lure of

holiness triumphed over cleanliness and I followed my classmates towards the

chapel.

Sitting in the softly lit chapel I close my eyes and listen as

the organist dances his fingers and toes across pedals and keys, piping out a

new arrangement of a old hymn. I feel the stress of Greek class begin wash off

of me and I’m glad that I came. It was the right choice.

A harsh voice from somewhere near me interrupts my meditation.

I open my eyes to see an old, unfamiliar man one row ahead of me staring at me

as if I had just insulted his wife. Two women in their mid-twenties stand next to him.

“Excuse me?” I ask, not sure that I heard what I thought I

heard..

“I said, ‘Take off that hat.’ Don’t you know where you are?”

I’m suddenly aware of the baseball hat that I threw on before

leaving the apartment. I completely forgot that I was wearing it. Personally, I

never understood why it was okay for women to wear hats in church but it was

disrespectful for men to do so. The practice has more to do with cultural

expectations than with spiritual guidelines. But I don’t want to cause anyone

to be upset.

“Oh, thanks,” I say. “I’ll be sure to take it off before the

service starts.”

He leans over the pew in front of me putting his hands on the

back of the polished wood seat. “Take it off now or I’ll take it off for you.”

His eyes began to bulge behind his wire rim glasses. His face was getting

redder by the second.

“Who is this old man is and what he’s doing in chapel?” I

wonder to myself. I imagine he lives in

the neighborhood and doesn’t have anything else to do on a summer day in August

except come to the seminary and grouch at the state of pastors-in-training.

“Jeez. Don’t get you underwear in a bunch,” I tell him. I look

him in the eye as slowly reach up to take off my hat and then place it

carefully next to me on the pew. “I’ll take it off just for you. Have a seat

and relax.”

I can honestly say that I’ve never seen anyone so apoplectic

in all my life. He can barely contain himself. I look at the women standing

next to him. I watch as their expressions change from fearful disbelief to

insulted dignity. Who are these people and why are they bothering me? They sit

down in front of me and I can tell they are fuming. I spend the duration of

chapel looking at the backs of their heads, annoyed that they ruined whatever

chance I had at finding some peace.

Following chapel I pick up a cup of coffee in the cafeteria and

find a table where some of my classmates have gathered. I sit down and tell

them about the crazy old man and this threats. I tell them what I said. When I

see that he is sitting at a table across the cafeteria with the two women, I

point him out.

“That’s Professor Harrisville,” someone at the table whispers.

Now everyone at the table has that look of fearful disbelief that the women had

in the chapel. “You said that to

Harrisville?”

Professor Harrisville had a reputation of being one of the

toughest professors at the seminary. It was then, and only then, that my Greek-fried

brain connected the dots between an “old, white guy at a Lutheran seminary” and

“Professor.” How could I have missed it? Now I understood the looks on the

women’s faces. I was an idiot who had just shortened his career at the seminary

by four years. It was over before it even began.

I wish I could finish this story by telling you that I faced

my mistake and went to ask forgiveness. But I didn’t do that. I was certain that

this incident would be the topic of discussion in the faculty lounge and that

every professor would have their eyes on me. A phone call to my dad convinced

me to stick it out for a year and see how things went. I spent that year, and

the next, fastidiously avoiding Professor Harrisville. My third year I was away

from campus on internship. By the time I returned for my senior year he had

either forgotten the incident or didn’t realize that I was the impudent student

who suggested that his crankiness was caused by wedged undergarments.

Labels:

bad days,

chapel,

errors,

hoops,

lessons,

mistakes,

professors,

remarks,

resolve,

school,

seminary

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)